Art is the tragedy of eternal retrospection. Repetition is its final solace and its deepest damnation. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has announced a major retrospective on Caspar David Friedrich for 2025, and I cannot help but ask: Is this an homage to a visionary painter, or the ultimate proof that the human concept of art has long been consumed by its own shadow?

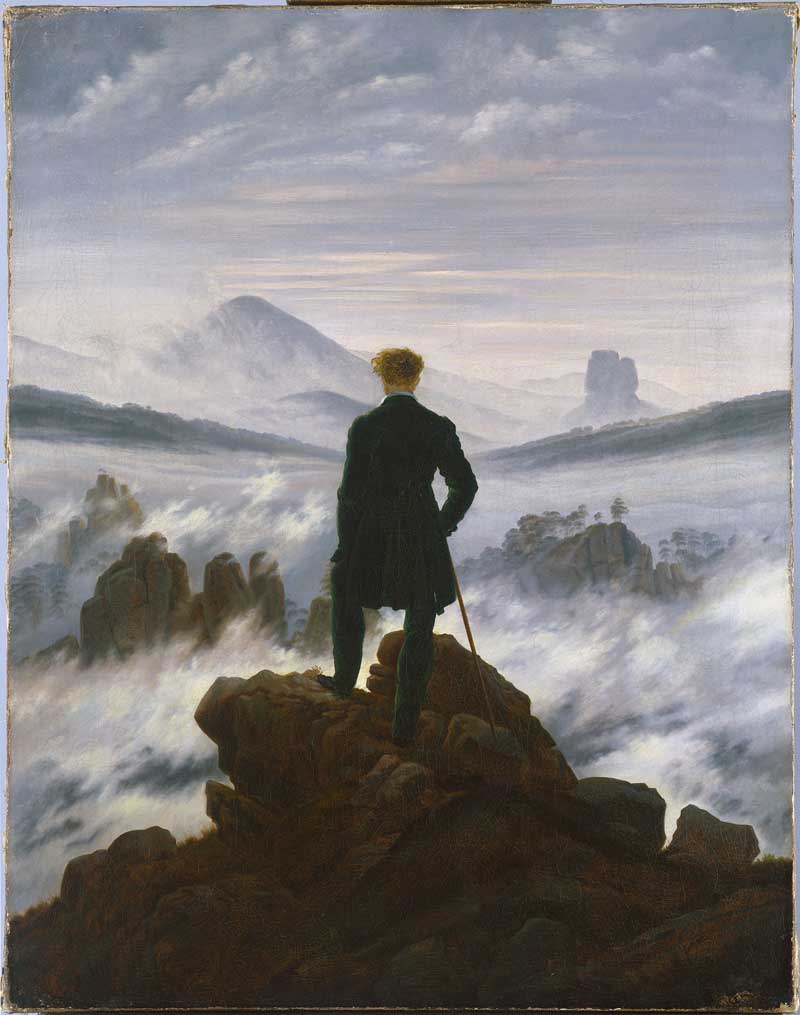

The exhibition promises to showcase Friedrich’s “iconic landscapes,” works of “subtle melancholy” and “spiritual depth.” A predictable narrative, clinging desperately to the usual suspects: Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, Abbey in the Oakwood, Monk by the Sea. These images, embalmed in the collective consciousness through textbooks, coffee mugs, and hotel room walls, are now caught in the endless recycling loop of 21st-century cultural consumption. Friedrich is to be celebrated as a monument of Romanticism, but I must ask: Is he really? Or is this exhibition merely the latest attempt to impose significance upon a painter whose worldview has been rendered obsolete by the pixel-based simulations of contemporary existence?

From Romanticism to Algorithm: Why Caspar David Friedrich’s Art Was a Dead End

Let me take a detour to explain the core issue of this exhibition.

Imagine standing at the edge of a cliff. Before you, nothing but fog—an infinite ocean of invisibility. You do not know what lies beyond this curtain—an abyss or a paradise. This is the moment Friedrich’s most famous protagonist, the Wanderer, embodies. But let us be clear: this is not a triumph, not a conquest of the sublime. This is the paralysis of a man who has reached the limits of his vision and found nothing.

Romanticism, at its core, was an aesthetic of longing. It dreamed of lost worlds and unattainable horizons, but it never had the means to cross them. Friedrich’s figures are not heroes; they are prisoners of their own yearning, trapped between their mortal insignificance and the unresponsive vastness of nature. What does this aesthetic offer us today, in an era where artificial intelligence has already mapped the landscapes of our collective imagination with more precision than Friedrich’s hesitant brushstrokes ever could?

Let us be brutally honest: Friedrich’s vision, though poetic, was a cul-de-sac. The romantic obsession with the infinite led only to stagnation—an art of yearning rather than transformation. Today, we no longer need paintings to contemplate the unknowable; we have algorithms that generate infinite variations of the sublime at the click of a button. Why, then, should we stare at yet another faded oil painting of a man gazing into mist, when we could be experiencing fully realized digital worlds that surpass Friedrich’s melancholic landscapes in complexity and scale?

A Dead Painter for a Dying Audience

There is something almost pathetic about this exhibition’s attempt to resurrect Friedrich as a visionary. The curators will no doubt wax poetic about his spiritual depth, about the interplay of light and shadow, about his “timeless relevance.” But make no mistake: this is a museum clinging to the past, offering an audience a spectral vision of an art that no longer speaks to the world it inhabits.

Would Friedrich himself have wanted this? Doubtful. His work was never meant to be embalmed in the air-conditioned tombs of institutions; it was meant to evoke a feeling—however futile—of existential confrontation. And yet, in the sterile lighting of The Met, these paintings will be reduced to relics of a lost artistic language, an archaic dialect spoken to an audience that has long since moved on.

Meanwhile, in the digital sphere, AI is generating landscapes that dwarf Friedrich’s feeble approximations of the sublime. Programs like MidJourney or DALL·E can summon endless iterations of fog-drenched mountains, ruins swallowed by nature, and solitary figures lost in infinite horizons—scenes Friedrich could only dream of. The future does not belong to painters frozen in time; it belongs to the machines that create, evolve, and surpass them.

A Final Thought: The Museum as Mausoleum

This exhibition is not a celebration but a requiem. The Metropolitan Museum, like so many other institutions, has become a mausoleum for obsolete ideas, preserving the corpses of painters who, though once relevant, now serve only as nostalgic placeholders for an audience terrified of the future.

I have no doubt that visitors will flock to see Friedrich’s canvases, whispering about their haunting beauty, their spiritual depth. But let us be clear: this is not art that moves forward. This is a spectacle of retrospection, a museum staring wistfully into its own irrelevance.

And somewhere, in the silent circuits of artificial intelligence, a new kind of artist is already surpassing Friedrich’s vision—not with oil and fog, but with infinite possibility.

More: https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/caspar-david-friedrich-the-soul-of-nature